a happenstance case study and tangent

A recent encounter with a discarded stove allowed me to think about what could’ve been or perhaps could be in a more sustainable future – if we could build consumer goods to last, end discontinuation, or use more standardized interchangeable parts.

I have an O’Keefe and Merritt oven ca. 1970s and over the years it started showing increasing wear. The burner knob label paint was wearing off the front panel and got worse every time I tried to clean it. The glossy white finish on top started coming off leaving raw, rusty metal spots and the burner plates had caked on carbon and rust. But it still worked. I’d occasionally consider fixing it up, but it’d involve taking it apart, spending $100s on powder coating and figuring out how to get the front panel labels re-printed. Seemed more trouble and expense than it was worth and so it sat there getting worse

Then one day my husband said there was a stove like ours in the trash area. I live in a big apartment/condo complex and some of the units have common built-ins and appliances, either from original installations or offered over the years as upgrade packages. So we live in this little microcosm of standardization where it’s totally possible to find someone throwing out the exact part you need or navigating the same odd window specs or broken furnace. The discarded stove was the exact same model as ours but in better shape. So we ended up unscrewing a couple panels and just swapped them out with the burner plates. Good as new! Or good condition vintage anyway. I even found the oven light button, previously disconnected and covered behind the old front plate.

This got me thinking as a designer, a bred American middle class consumer, and a human who lives in increasing dread of the climate crisis… why can’t more things work like this? This was so much easier, less expensive and less wasteful than common alternatives. There must be something between continuous disposal/consumption and post-apocalyptic austerity. What if product styling changes either came much slower or were expressed in pieces compatible with older models? And if you didn’t want to change out the styling or held onto something long enough for it to be vintage, couldn’t the manufacturer or a 3rd party continue to make replacement parts? What if there were industry wide standards so that parts worked with products from other manufacturers? Maybe you can return old pieces for refurbishing. Or maybe some companies could focus on function and others on styling. And ALL of it could be built to last.

I know this is how salvage works and cars basically work like this. It’s what communities not swimming in renovation or flipper cash have been doing for decades. But there is so much overwhelming momentum and hypnotizing convenience pushing us away from that at this point that I think it has fallen not just out of habit but out of collective awareness. It has been replaced by systems based on creating desire before and at the time of purchase with little thought to long-term use and maintenance and no regard for what you have now. Designers, technologists, marketers and consumers are all driven by sales to focus their attention on that part of the product cycle. However, maybe enough people can work to refocus attention from “what/where to buy” based on style to “what to look for and how to maintain” based on quality or sustainability. There are even communities who socialize their maintenance work. In Djenné, Mali, they make a festival out of weatherproofing their Grand Mosque.

We’d likely need manufacturing standards by ANSI, ISO or a product design trade group. Perhaps these exist but maybe there’d need to be external regulation or consumer pressure to take standardization more strictly and comprehensively. There would need to be movement in the lifestyle consumption complex from Pinterest to Instagram to HGTV to shift from encouraging a never-ending cycle of gutting, disposal and remodeling to ongoing maintenance, economy and quality. And with our current lack of government or industry leadership for transitioning our economy, designers and consumers might have to organize to push for another way of designing and purchasing products.

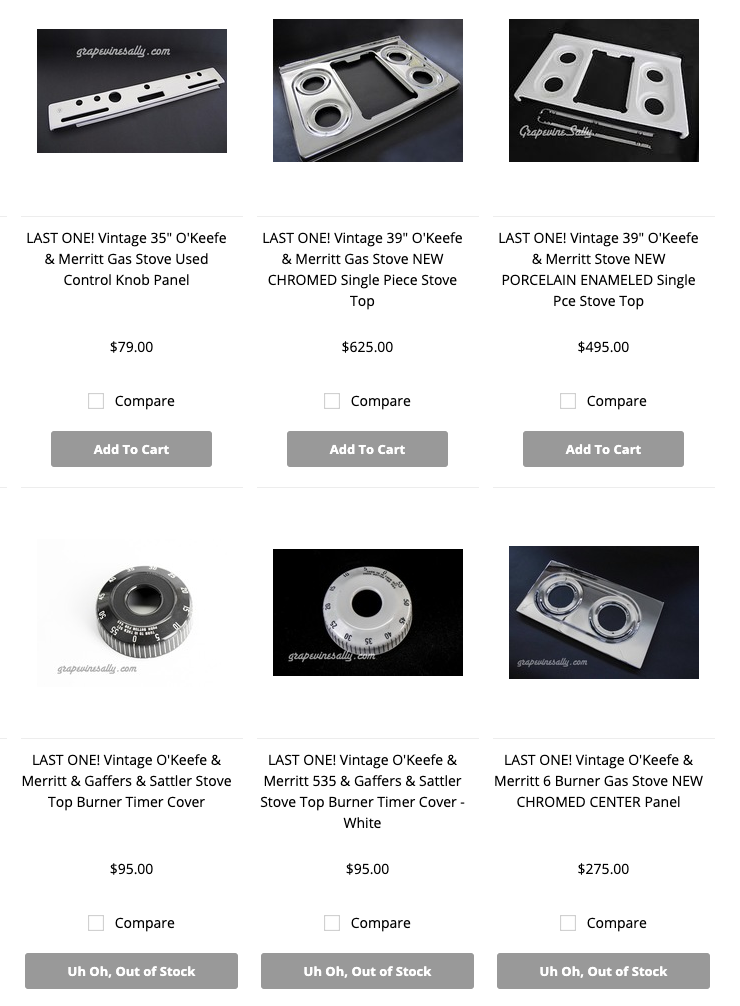

There is some movement in this direction and it’s more feasible with older products as there are vintage suppliers and re-fabricators. But we’ve drifted a long way from this reality for most goods. Many products like clothes, toys and even furniture are now built to be nearly disposable. For modern global companies, sustainability is largely empty marketing. Their focus is on recycling or even hypothetical recyclability rather than reducing production or increasing quality. And companies like Apple and John Deere actively fight the ability to repair their products. Further, while these products would be more economical in the long-run, they’d have bigger upfront costs that would give many already strapped consumers sticker-shock.

I’m not sure if or how this could change, but I think it’s a compelling possibility to imagine as consumers and designers. In the design culture I grew up with, the main focus was innovating on form, not much about sustainability or the macro-economic forces driving design. The 80s and 90s saw the height of postmodernism and the ascension of its companion neoliberalism. The depth of the climate crisis wasn’t widely known. The highest value and even a kind of moral integrity was attributed to individual designers who could realize their visions without compromise. However, too much of value may get compromised in pursuit of form. Or value may get lost entirely while deceptively chasing the signifiers of it. Designers have often taken pride in their role shaping the world around us, but we should check in with how that’s going. Far from being all-powerful, we might only play a rather confined role in complex, interconnected systems.

In the spirit of the Reconstrained Design Manifesto, it’s worth trying to work within the constraints of humanity and ecology and not simply try to crush it on a client or employer brief. I feel a sudden interest in the vanguard of specification standards, supply chains, reuse, durability and repairability. After crushing that, maybe we can explore the boundaries of color, texture and shape. Maybe there will even be some humans around to appreciate it.

No comments yet.